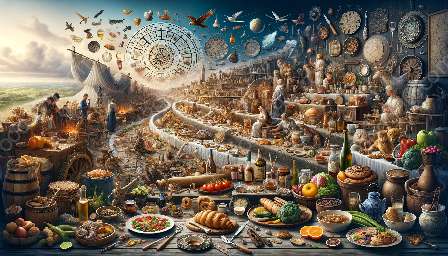

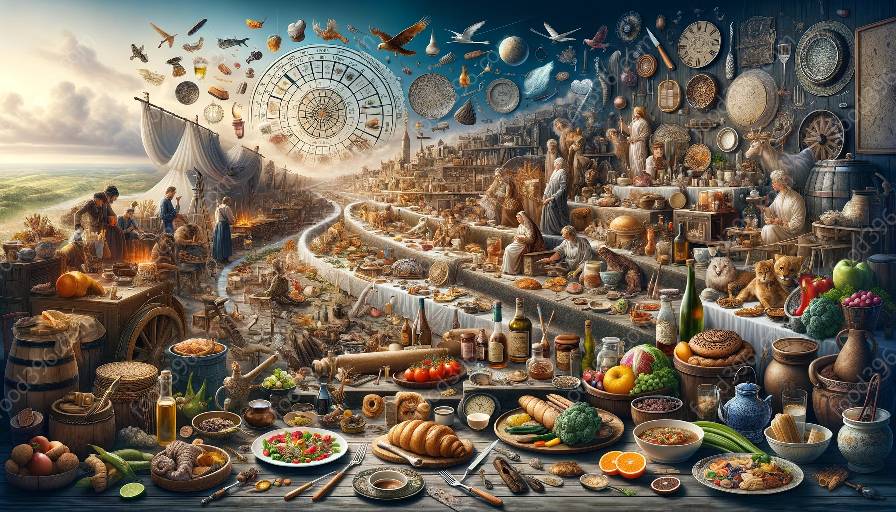

Japan's rich cultural heritage is embodied in its vibrant festivals and celebrations, many of which are characterized by an abundance of delicious foods. The historical role of food in Japanese festivals is deeply intertwined with the country's cuisine history, reflecting centuries of tradition and religious significance.

The Historical Context

Japanese festivals, known as matsuri, have been an integral part of the country's cultural fabric for centuries. These events serve as opportunities for communities to come together and honor local deities, express gratitude for the harvest, and celebrate seasonal changes. Food plays a central role in these festivals, symbolizing the connection between humans and the natural world, as well as serving as offerings to the gods.

Shinto and Buddhist Influences

The historical role of food in Japanese festivals is deeply rooted in religious traditions, particularly Shinto and Buddhist beliefs. Shinto, Japan's indigenous spiritual practice, places a strong emphasis on purification rituals and offerings to kami, or spirits. In this context, the presentation of food at Shinto festivals is a way of showing respect and gratitude to the gods, as well as seeking their blessings for the community's well-being.

Buddhist festivals in Japan also feature a wide array of foods, often associated with spiritual symbolism and historical anecdotes. For example, osechi ryori, a traditional Japanese New Year's cuisine, is filled with symbolic meanings and is often offered to Buddhist altars during the first three days of the year. Each dish in the osechi ryori represents a wish for good fortune, health, and prosperity in the coming year.

Symbolism and Tradition

Food served during Japanese festivals is often imbued with symbolic meanings that reflect the cultural and historical significance of the event. For example, mochi, a type of rice cake, is a staple of many Japanese celebrations, including the mochitsuki ceremony, where families gather to pound steamed rice into a sticky, elastic mass. The act of making mochi is not only a communal bonding experience but also symbolizes the exertion of physical effort to drive away misfortune and purify the household.

Sweets, known as wagashi, hold a special place in Japanese festival cuisine. These confections are meticulously crafted to reflect the seasons, with shapes and colors symbolizing nature's beauty and the passage of time. Wagashi also serve as offerings at tea ceremonies and are an integral part of many traditional Japanese celebrations.

Seasonal Delights

Japanese festivals are closely tied to the changing seasons, and the foods served at these events often reflect the bounties of nature during specific times of the year. For example, cherry blossom festivals, known as hanami, feature a variety of seasonal treats, such as sakuramochi and hanami dango, which are enjoyed under the blooming cherry blossoms. Similarly, autumn festivals highlight the harvest with dishes like tsukimi dango, or moon-viewing dumplings, and other seasonal specialties.

Modern Traditions

While the historical role of food in Japanese festivals continues to be honored, modern celebrations have also incorporated new culinary elements. Festivals such as the Sapporo Snow Festival and the Sapporo Autumn Festival showcase a wide range of contemporary and traditional Japanese foods, attracting both locals and international visitors eager to experience the country's diverse culinary offerings.

Furthermore, food stalls and street vendors have become ubiquitous at many Japanese festivals, offering a smorgasbord of regional specialties, from takoyaki (octopus balls) to yakisoba (stir-fried noodles). These beloved festival foods reflect the cultural diversity and evolving tastes that continue to shape Japan's culinary landscape.

Conclusion

The historical role of food in Japanese festivals and celebrations not only reflects the country's rich culinary heritage but also serves as a testament to its enduring traditions and cultural resilience. From ancient rituals to modern customs, the diverse and symbolic foods enjoyed during Japanese festivals continue to uphold the deep connection between food, community, and spirituality.